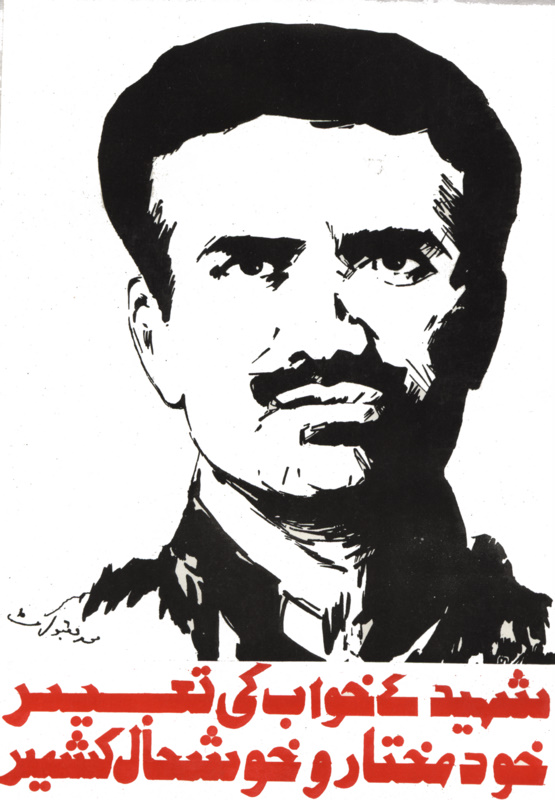

MAQBOOL BUTT: HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND LEGACY.

Continued

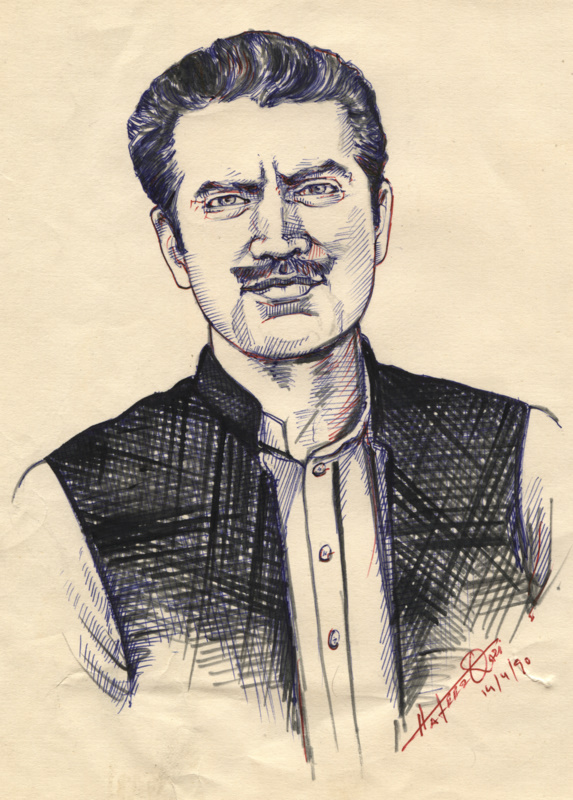

This historic pattern of bondage can be summed in one word: Movalgi. Movali in Kashmiri language is a vagabond. Movali in Arabic means a non-Arab. Understanding the significance of this one word in context of Kashmiri society helps to explain the dilemma of leadership in Kashmir. Islam in Kashmir spread with efforts by learned Sufi scholars like Shah Hamdan. By their personality and intellect, the scholars converted the rulers of Kashmir to Islam. However, with the advent of Islam in Kashmir the existing social order did not change, it maintained its class structure. Progeny of the men from the Arab-world, soldiers seeking fortune and preachers in search of converts to Islam, married with the elite of Kashmir and merged in the social class hierarchy in Kashmir. Indeed the social class structure in Kashmir is flexible and mobility within hierarchy is common. Yet, there are certain biases that are hard to overcome, one of these is leadership role. The labor classes of urban areas and village peasant are not easily accepted in the leadership role. In Kashmir, the divine right of the womb still rules. The climb through the ranks of upper class in Kashmir is historically gained by the powerful by acquiring wealth first and then through matrimonial alliances. In Kashmir, society continues to be dominated by dynastic religious leaders, landlords, and the wealthy business houses. The democratic governance in Kashmir, Awami-Raj during the second half of the century in Kashmir was at best democratic despotism. Sheikh Abdullah got the mantle of political leadership only after the then Mir Waiz (head priest) of Kashmir supported him. Support of the Mir Waiz gave Abdullah the beachhead to launch his agitation against the Dogra dynastic rule. Over time, Abdullah, by the force of his personality and his political organization, National Conference, usurped Mir Waiz. Abdullah by the end of his fifty-year political career established his own dynastic rule for Kashmir. Abdullah had began in 1930 as the brave "lion" of Kashmir to fight for the rights of the down trodden Kashmiri masses, fifty years later he was the patriarch of a Raj centered around his family. Soon after, Abdullah had his son "elected" as president of National Conference Party and then "willed" the "governance of Kashmir" to him. The family Raj continues Abdullah’s grand son now awaits in the wings, to step into his father's shoes as the next head of government in Kashmir. Abdullah used nepotism and corruption, the two instruments by which the elite maintains their control. Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, who followed Abdullah, perfected this ancient system into a modern regime of reward and punishments for governance in Kashmir. The tradition of corruption and nepotism is among all shades of politics in Kashmir. Maqbool Butt was not born in the upper social class; he did not seek wealth by corruption, or marriage to be among the upper classes. He was not an opportunist and he did not compromise his values. So Maqbool Butt's attempted revolution to cleanse the historic legacy of bondage in Kashmir was like a rain shower attempting to make a swamp full of algae into a fresh water lake. Maqbool Butt left Kashmir for Pakistan a young man; he was in his twenties. In Kashmir and in Pakistan his environment was constrained. He had no mentors. As a young man he witnessed and was influenced by the militant revolutions of the time. He wanted emancipation of his countrymen so he used the methods and means available to him. Two attempts at militancy, first in 1966 and second in 1975 got him twelve years of jail time, two in Pakistan and ten years in India. During his eight years of incarceration at Tihar Maqbool Butt may have received just one letter from his "watan". Writing to Malik Mohammed Asgar, on August 18, 1981 Butt writes that for a man of faith, the best way of life is that which is spent in eradicating falsehood and for seeking justice and the best death is that which comes while struggling on this way. Maqbool Butt did just that. He assumed and carried out his personal responsibility, as best as he could. Kashmiri viewed incarceration of Maqbool Butt as a matter alien to their day to day existence and thus ignored it. While Kashmiri’s admired Maqbool Butt for his valor, he got little support when he needed it. So it is today, without support, as Maqbool Butt was left by a vast majority of Kashmiri’s, "Movali" youth of Kashmir continue to perish, alone. Light of Hope If instead of sitting on the sidelines watching the youth of their homeland getting wasted in killing sepoys of India, if all Kashmiri’s join ranks; if the "carrier-politicians" in Kashmir instead of calling on the conscience of the world would call on their own; instead of tearing down others for their differences, they would strengthen each other focusing on their commonality, I often ponder, how different Kashmir could be. For me this year February 11 was a day to fast, to remember the sacrifice of Maqbool Butt and other martyrs. It was a day I set aside to pray for the ability to do my share to better my community. And on February 28, Maqbool Butt's birthday, I found myself lighting a candle at dusk in his memory. It was for me, and I hope will be for others too, a Festival of Freedom (Independence Day Lights) visualized by Maqbool Butt. Azmat Khan in his essay recalls Maqbool Butt words from a letter written to Raja Muzzaffar on August 15, 1981: "It is a matter of pride for me that not only difficult times and awkward circumstances have failed to put out the light of hope, which I have lit with sacrifices, but many more lights are now glowing because of this candle. If this pace continued the day is not far, Insha-Allah, when that flood of light shall brighten up our motherland in a way that we shall be able to name it the Festival of Freedom (independence day lights)".

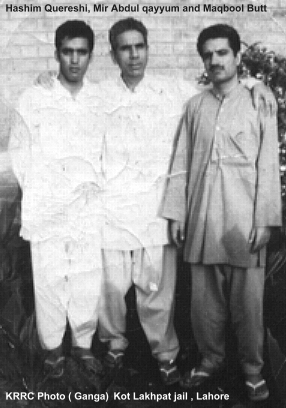

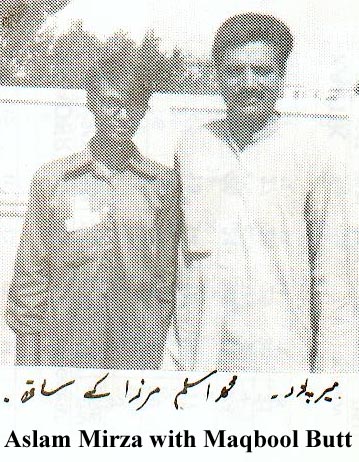

Butt continued to nourish his ideas of the armed resistance. They came to head on January 30, 1971 when an Indian airline airplane, named Ganga was hijacked from Srinagar to Lahore by two JKNLF operatives. One of the Ganga highjackers, Hashim, - both were cousins, Hashim and Ashraf Qurashi - had two years earlier on a visit to Pakistan met Maqbool Butt. Qurashi joined JKNLF. He was asked to return to Kashmir and organize underground cells of JKNLF in Kashmir. The Ganga Highjackers, at first were hailed as heroes in Pakistan, until things became unraveled. The hijackers burned Ganga. In retaliation, India revoked permission for Pakistan to flights over Indian airspace. That eventually helped to dismember Pakistan and give birth to Bangladesh. Alastair Lamb in his book, Kashmir A Disputed Legacy 1846-1990, suggests that the hijacking was Indian engineered, because among other things the highjackers "in a hurry burned Ganga". Raja Muzzaffar who was there, disputes this, and maintains that the Pakistan police official, Sardar Abdul Vakil, instructed the destruction of the airplane. Vakil was concerned about the law and order situation created at the Lahore Airport by the public gathered to witness the hijacking drama. He instructed the Qurashi cousins to burn the plane. In his statement before the Special Court on Ganga Hijacking, K. H. Khurshid who served as President of Azad Kashmir from May 1, 1959 to August 5, 1964 and was also present at the airport collaborates Raja Muzzaffar’s assertion. Khurshids statement in part reads: "As I have already said, Sardar Vakil Khan, S.S.P. Lahore told Hashim Qurashi in my presence to burn the hijacked plane." Apparently, the establishment leadership of Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah on the Indian side in a letter and Sardar Quyum on the Pakistani side in newspaper articles suggested that the Qurashi cousins worked as Indian agents, in order to discredit the JKLF. leadership. Azmat Khan notes that the Indian Authorities had arrested Hashim Qurashi on his return from Pakistan. The Indians apparently spared his life "on the promise that he would help them recognize expected 'infiltrators' from Pakistani side. ... The Indian BSF fell for his story and not only spared his life but also allowed him to travel freely, which subsequently helped him complete his mission." By April 1971 Maqbool Butt, the Qurashi cousins, and all of JKNLF cadre in Azad Kashmir, were in Pakistani jails. They were charged and tried for treason against Pakistan. Two years later, in May 1973 Maqbool Butt and most of JKNLF members were released. The Lahore High Court declared them as, " patriots fighting for the liberation of their motherland", notes Azmat Khan. Hashim Qurashi remained jailed and was later released on appeal.

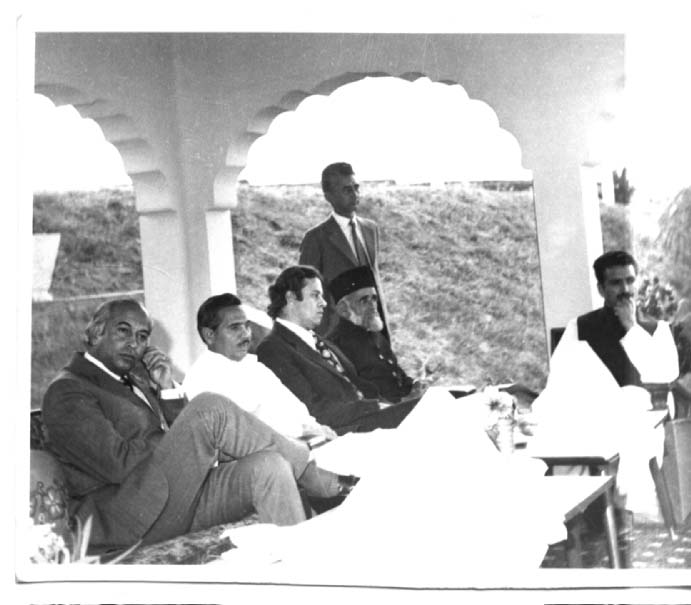

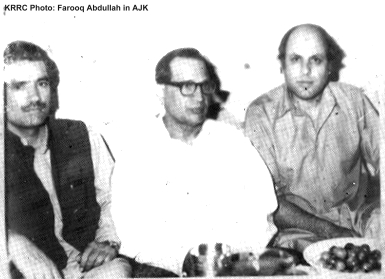

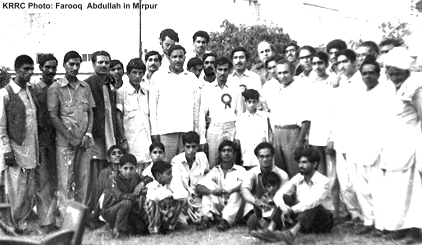

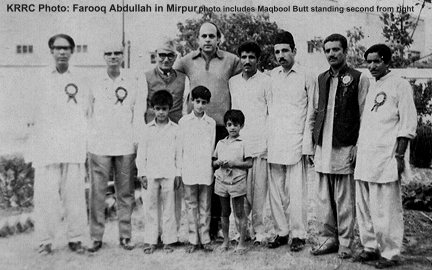

At the end of Bangladesh war Pakistan was a defeated nation. Zulfikar Bhutto, the new Prime Minister of dismembered Pakistan, under the terms of his surrender agreement, the Simla Accord, agreed to rename the cease-fire-line in Kashmir as the Line-of-Control. This implied confirming the status quo on Kashmir. On his return from Simla, Bhutto proposed to make Azad Kashmir a province of Pakistan. Maqbool Butt spearheaded Kashmiri opposition to this proposal. On the other side of the border in Indian occupied Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah reconciled with Indian occupation of Kashmir. Under the terms of his agreement with India, called the Indra-Abdulla Accord, he gave up on the quest for freedom for Kashmir. According to Raja Muzaffar, Bhutto told Farooq Abdullah, who visited Pakistan in 1974, that Pakistan could not do anything for Kashmir for decades to come and that Sheikh Abdullah should take what ever he can get from India. Victoria Schofield in Kashmir Under Crossfire quotes Farooq Abdullah’s observations of his 1974 visit to Pakistan, " The entire bureaucracy of Pakistan and Bhutto’s secretary himself told me that a final solution has been arrived at; there can be nothing more. What we (the Pakistanis) have got (in Kashmir) we are keeping, what they have got they are keeping, and that is how it is."(page 214).

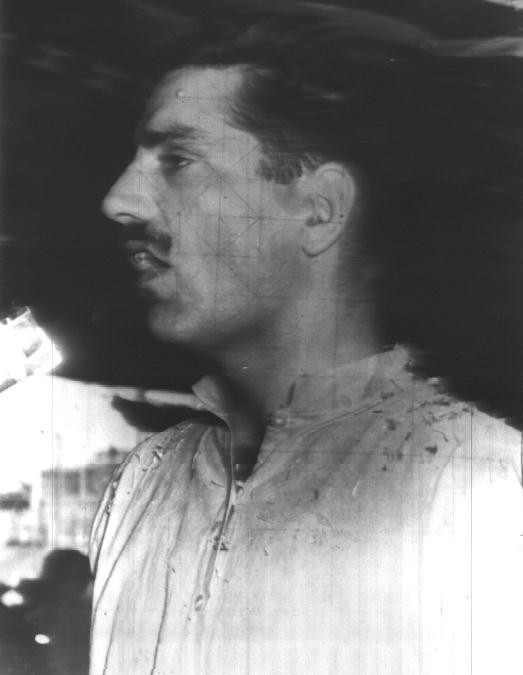

For giving up his quest for Kashmiri freedom, Abdullah received the reigns of government in Kashmir. The opposition to 1975 Indra-Abdulla Accord in Kashmir was widespread but uncoordinated. Abdullah the undisputed patriarch of Kashmiri politics contained the opposition. Political activity for freedom of Kashmir in Azad Kashmir was at a standstill. To restart his militant revolution Maqbool Butt again crossed into the Indian side of Kashmir in May 1976. He was again captured. This time the Indian central government removed Butt to the infamous Tihar Jail in India. Maqbool Butt did not come out of Tihar. He remained a prisoner for eight years, most of the time in solitary confinement. Then he was hung to his death on February 11, 1984 and buried in the jail yard.

More On Letters

Thirty-three out of thirty-nine letters in Shaur-e-Farda are written from Tihar Jail, starting from January 9, 1974 and ending on September 8, 1983. The letters are written to nineteen individuals. Six to Dr. Farooq Haider, four each to Akram Ullah Jaswal, Mohammed Araf and Ghulam Sarwar Malik, three to Arshad Mahmood Ansari, two each to Mohammed Asgar Malik, Abdul Aziz Butt, Ghulam Sarwar Mian and Raja Muzzaffar and one each to ten others.

Maqbool Butt's attachment to his homeland and understanding of the aspiration of Kashmiri people comes through particularly from two letters. First, one is the fifth letter in the book, from Camp Jail Lahore to Mohammed Yusuf Zargar, dated January 30, 1973. This is one of the long letters and reads like a chapter of well-written storybook. Butt reminisces his days in Baramulla, he describes the beauty of the town and the simple pleasures that he missed and longed for in the jail; Kashmiri salt tea, kulcha and sag. He reminds Zargar of tortures suffered and forced exile of Kashmiri freedom fighters at the hands of Indian authorities. Selfless devotion to the cause of freedom and devotion of his friends kept Butt's hope alive, he tells Zargar.

A particularly poignant letter in Shaur-e-Farda is from Camp Jail in Lahore dated April 2, 1973. This letter is reply to a teenaged girl, Azra Mir. Azra's father G.M. Mir was jailed with Butt by Pakistan authorities. Butt consoles Azra for the hardships she and her family face with the absence of their father. Butt writes about his own childhood, and the sufferings in his village at the hands of landlords during the Dogra Raj in Kashmir. Butt describes for Azra the hardships Kashmiri’s had to face during the oppressive Dogra rule and how the village children, including Butt helped the villages to face the oppression. He describes hardships that forced Kashmiri’s to leave families and labor as beasts of burden in Indian Plains to feed their families; how the Kashmiri traders had to do 'pherri' and suffered indignities as 'hatoo'. He describes the freedom struggle from 1930 to 1947. The era of sacrifices did not end in 1947, Butt continues to tell Azra that children of Kashmir like every slave nation have to bear the oppression of zalim aakas (tyrant masters) and also to fight shoulder to shoulders with their elders. Azra in her letter must have expressed her hurt at being branded as a family member of an Indian Agent. Butt explains to her that the people of Pakistan did not label him and his colleagues as Indian spies but that the ruling class of Pakistan had. The ruling class for 25 years denied freedom and democracy in Pakistan, Butt explains. The ruling class to maintain their power had even cut up Pakistan. Butt reminds Azra that the people of Pakistan have and will continue to support Kashmiri emancipation struggle.

In the concluding paragraph, Butt reminds Azra that education is the true wealth of a human, a treasure that can never be stolen nor wasted. And, without education, man is an animal. Therefore, he advises Azra to be more attentive to her studies. This 3,000-word letter is the longest in Shaur-e-Farda. It is a good history lesson for the young generation.

During his captivity of eight years at Tihar jail, mostly in solitary confinement, Maqbool Butt, it seems, received only one letter from Srinagar. The letter is from Mian Ghulam Sarwar. In his reply to Sarwar on August 7, 1981 Butt in a poetic prose expresses his joy at receiving a letter from "watan" (homeland). Sarwar had enclosed in his letter press-clippings about Butt. Butt responds using a quote in English: "The end of communication is the beginning of violence where communication stops, there remains only beating, burning and hanging". Butt notes that his captors, done with beating and burning, are now getting reading for hanging. In this letter also, like most others Butt expresses his resolve to face consequences and asks Sarwar to pray that God will give him courage to be steadfast. This is the only letter with a hint of complaint in that Butt asks Sarwar that if his captors are so sure of his crimes then why do they keep all the files under cover. Butt was not despondent and took every opportunity to confront his captors. So it is in his letter to Malik Ghulam Sarwar dated August 15, 1981 that he accepts the suggestion to file a writ petition with the Supreme Court of India.

On May 13, 1978 in his last letter to his son Shaukat Maqbool he writes to never doubt Gods mercy, not to bow down to a tyrant, to remain stead fast: " Allah Tala Ki Rahmat See Kabi Bi Na Umaid Nahi Hoona Chaiya.... Wooh Insan Hee Kya Goo Halat Kee Samni Guthni Teek Dee. Pass Himmat Aur Hoslee Ko Hamesha Apna Sahara Banaye Rakhee Aur Halat Ka Mukabala Mardana War Kareen."

All letters in Shaur-e-Farda except one are written in Urdu. The only letter written in English is addressed to Mia Ghulam Sarwar. Acknowledging Sarwar's Eid Greetings telegram, Butt on October 15, 1981 wrote: "I cannot but appreciate your choice of remembering me on this auspicious occasion, which symbolizes the offer of improm (sic) sacrifice for ones faith and ideals. History certainly does not offer a better example than the one prophet Abraham to idealize mans devotion and dedication to the cause he cherishes as well as his perseverance, when on trial, in the pursuit of his beliefs. Given our weaknesses, we may not strive to such levels, yet we can surely follow in the footsteps of such great men at least according to our capacities. This, I think is an obligation which no concencious person, least of all from amongst our people can afford to forgo for because (Butt continues in Urdu: Yeh Daur Apne Abrahim Ki Talash Me Hai Sanam Kuda Hai Jahan La-Illa-Ha-Illah) translation: this period is our search like Abraham for one and only God."

The last letter in Shaur-e-Farda is dated September 8, 1983, about 120 days before his execution. This is the fifth and last letter to Dr. Farooq Haider. It is written in an upbeat manner. Butt describes the progress in his defense case. He had filed a writ petition in the Indian Supreme Court. The court had upheld his request to instruct the Kashmir authorities to provide records related to his trial case. Butt informs that his lawyers consider their case is strong. Butt ends his letter by noting that he has left the results to God.

Maqbool Butt, Last Days

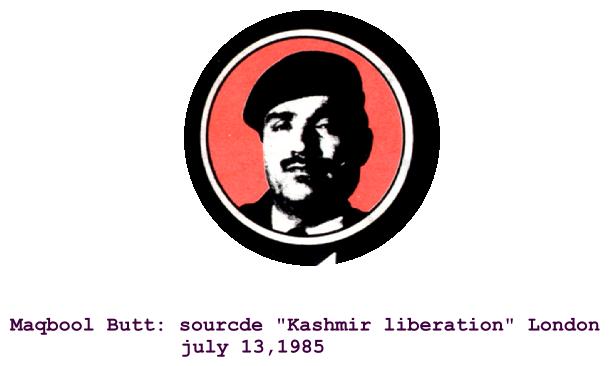

Azmat Khan in his account, Maqbool Butt (Shaheed) - Full Story notes that: "Difficult as it was the political campaign to ensure Maqbool Butt's release from prison never faded during the eight years of his custody." In addition to efforts in Azad Kashmir and Srinagar, protests were held in England. Amnesty International, Azmat Khan notes, "repeatedly appealed for his release from prison. (Amnesty International later declared him a 'Prisoner of Conscience'). All humanitarian appeals, however, fell on deaf years in Gandhi's India ".

On February 3rd 1984, notes Azmat Khan in England a previously unknown group calling itself the Kashmir Liberation Army (KLA) abducted an Indian Consulate staff member in Birmingham and demanded Maqbool Butt's release in exchange for his. The abductors killed the diplomat. In a tit-for-tat move, notes Azmat Khan, Maqbool Butt was hanged in Delhi, within four days of recovery of the dead body of the diplomat. He was hanged at dawn and buried within the jail premises. His family was not permitted to travel to visit with Butt. A day before his execution, all his known followers and sympathizers in Kashmir were kept in jails by authorities. February 11th every year now is "celebrated" in Kashmir as a day of protest strikes. Each year mythology of Maqbool Butt is expanded. Some write of messages from Butt conveyed in their dreams, others add rhetoric to his divine qualities. The rhetoric on divine qualities of Maqbool Butt could soon rank him among the historic "rishis" (sages) of Kashmir. The sages of Kashmir who are believed to have had vision so sharp that they could tell the sex of an unborn calf by one look at the pregnant beast. Maqbool Butt's legacy, to be.

Maqbool Butt was indeed a self-less son of Kashmir who devoted his life for emancipation of his homeland. He was not recognized and his mission remained unaccomplished in his lifetime, why? The answer may be in understanding the political and social environment of Kashmir. Kashmiri society has a feudal structure; individuals are not agents of change in a feudal society. Kashmiri’s depend on others to right the wrong, individuals accepting responsibility to make change is not their norm. In Kashmir change historically has come from was outside, and is brought about by outsiders. These characteristics together with appendages of nepotism and corruption are the core reasons of Kashmiri bondage.

This historic pattern of bondage can be summed in one word: Movalgi. Movali in Kashmiri language is a vagabond. Movali in Arabic means a non-Arab. Understanding the significance of this one word in context of Kashmiri society helps to explain the dilemma of leadership in Kashmir. Islam in Kashmir spread with efforts by learned Sufi scholars like Shah Hamdan. By their personality and intellect, the scholars converted the rulers of Kashmir to Islam. However, with the advent of Islam in Kashmir the existing social order did not change, it maintained its class structure. Progeny of the men from the Arab-world, soldiers seeking fortune and preachers in search of converts to Islam, married with the elite of Kashmir and merged in the social class hierarchy in Kashmir. Indeed the social class structure in Kashmir is flexible and mobility within hierarchy is common. Yet, there are certain biases that are hard to overcome, one of these is leadership role. The labor classes of urban areas and village peasant are not easily accepted in the leadership role. In Kashmir, the divine right of the womb still rules. The climb through the ranks of upper class in Kashmir is historically gained by the powerful by acquiring wealth first and then through matrimonial alliances. In Kashmir, society continues to be dominated by dynastic religious leaders, landlords, and the wealthy business houses. The democratic governance in Kashmir, Awami-Raj during the second half of the century in Kashmir was at best democratic despotism. Sheikh Abdullah got the mantle of political leadership only after the then Mir Waiz (head priest) of Kashmir supported him. Support of the Mir Waiz gave Abdullah the beachhead to launch his agitation against the Dogra dynastic rule. Over time, Abdullah, by the force of his personality and his political organization, National Conference, usurped Mir Waiz. Abdullah by the end of his fifty-year political career established his own dynastic rule for Kashmir. Abdullah had began in 1930 as the brave "lion" of Kashmir to fight for the rights of the down trodden Kashmiri masses, fifty years later he was the patriarch of a Raj centered around his family. Soon after, Abdullah had his son "elected" as president of National Conference Party and then "willed" the "governance of Kashmir" to him. The family Raj continues Abdullah’s grand son now awaits in the wings, to step into his father's shoes as the next head of government in Kashmir. Abdullah used nepotism and corruption, the two instruments by which the elite maintains their control. Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, who followed Abdullah, perfected this ancient system into a modern regime of reward and punishments for governance in Kashmir. The tradition of corruption and nepotism is among all shades of politics in Kashmir. Maqbool Butt was not born in the upper social class; he did not seek wealth by corruption, or marriage to be among the upper classes. He was not an opportunist and he did not compromise his values. So Maqbool Butt's attempted revolution to cleanse the historic legacy of bondage in Kashmir was like a rain shower attempting to make a swamp full of algae into a fresh water lake. Maqbool Butt left Kashmir for Pakistan a young man; he was in his twenties. In Kashmir and in Pakistan his environment was constrained. He had no mentors. As a young man he witnessed and was influenced by the militant revolutions of the time. He wanted emancipation of his countrymen so he used the methods and means available to him. Two attempts at militancy, first in 1966 and second in 1975 got him twelve years of jail time, two in Pakistan and ten years in India. During his eight years of incarceration at Tihar Maqbool Butt may have received just one letter from his "watan". Writing to Malik Mohammed Asgar, on August 18, 1981 Butt writes that for a man of faith, the best way of life is that which is spent in eradicating falsehood and for seeking justice and the best death is that which comes while struggling on this way. Maqbool Butt did just that. He assumed and carried out his personal responsibility, as best as he could. Kashmiri viewed incarceration of Maqbool Butt as a matter alien to their day to day existence and thus ignored it. While Kashmiri’s admired Maqbool Butt for his valor, he got little support when he needed it. So it is today, without support, as Maqbool Butt was left by a vast majority of Kashmiri’s, "Movali" youth of Kashmir continue to perish, alone. Light of Hope If instead of sitting on the sidelines watching the youth of their homeland getting wasted in killing sepoys of India, if all Kashmiri’s join ranks; if the "carrier-politicians" in Kashmir instead of calling on the conscience of the world would call on their own; instead of tearing down others for their differences, they would strengthen each other focusing on their commonality, I often ponder, how different Kashmir could be. For me this year February 11 was a day to fast, to remember the sacrifice of Maqbool Butt and other martyrs. It was a day I set aside to pray for the ability to do my share to better my community. And on February 28, Maqbool Butt's birthday, I found myself lighting a candle at dusk in his memory. It was for me, and I hope will be for others too, a Festival of Freedom (Independence Day Lights) visualized by Maqbool Butt. Azmat Khan in his essay recalls Maqbool Butt words from a letter written to Raja Muzzaffar on August 15, 1981: "It is a matter of pride for me that not only difficult times and awkward circumstances have failed to put out the light of hope, which I have lit with sacrifices, but many more lights are now glowing because of this candle. If this pace continued the day is not far, Insha-Allah, when that flood of light shall brighten up our motherland in a way that we shall be able to name it the Festival of Freedom (independence day lights)".

Written by This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.Kashmir Human Rights Foundation

1835 Apex Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90026.