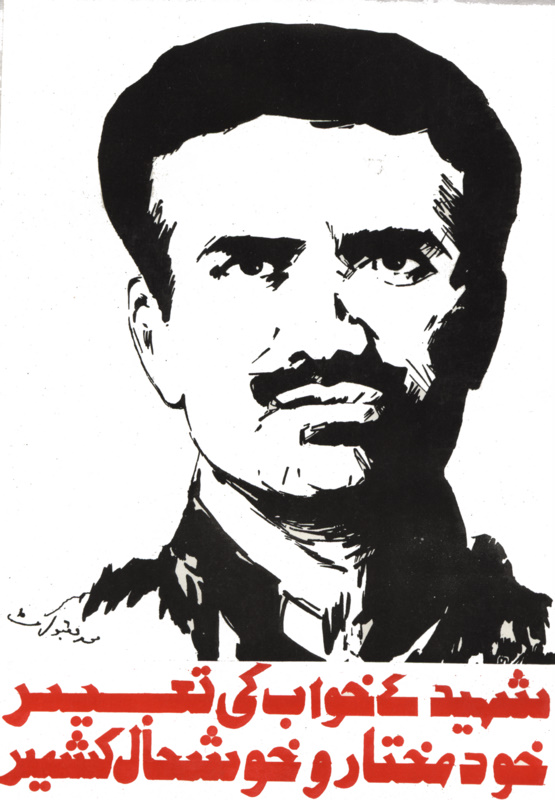

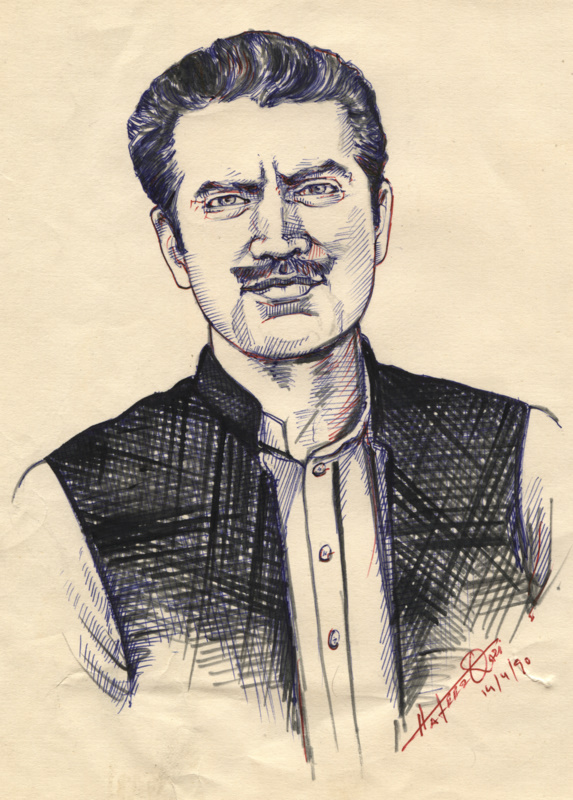

It outshines his fragmented legacy

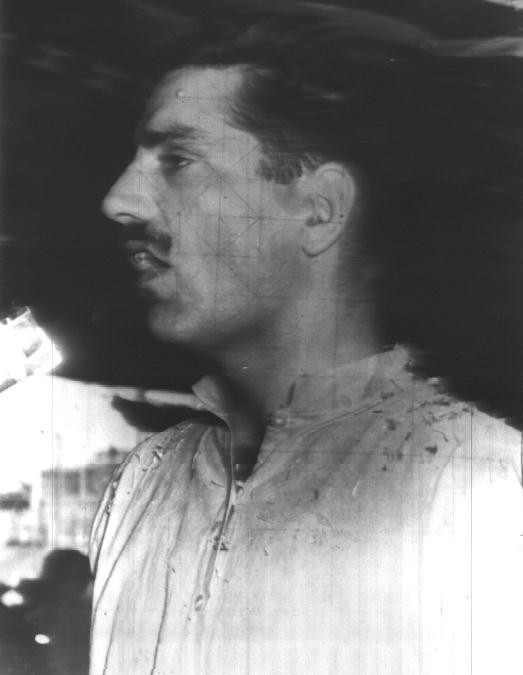

Maqbool Butt, whose 24th death anniversary falls today, chose to

struggle - and die-for his conviction rather than seeking to reconcile

sharply contradictory perceptions which his cult-ringed persona evoked

within and between the two halves of his divided motherland.

His debatable methodology aside, Butt remained consistently committed

to achieving an 'independent, secular, democratic, reunited (1947)

Jammu and Kashmir'. The entrenched political class on both sides of the

Line of Control detested and feared him for his romantic belief in the

correctness of his course. Governments in India and Pakistan saw him as

each other's 'agent' or tolerated him as a 'convenient' entity in the

game of one-upmanship, even as his political dream caught the

imagination of an upcoming generation.

A string of unconnected but instantly electrifying incidents and

coincidences, between 1967 when he was arrested for allegedly shooting

dead an India Intelligence man in North Kashmir and his execution in

Delhi's Tihar jail on February 11, 1984 just a week before his 46th

birthday, seemed to have charted the fateful course of his life. Butt's

sensational, mystery-shrouded escape (to Pakistan) from the Srinagar

central jail in December 1968 after being sentenced to death; the first

ever plane hijacking in the subcontinent in January 1971 by his

supporters; his return to and recapture in the Valley in 1976 and

finally the kidnapping and murder of Birmingham-based Indian diplomat

Ravindra Mhatre in February 1984 literally plotted the trajectory of

his meteoric rise and a tragic end.

The extent and nature of his actual involvement in causing some of

these crucial incidents of his life are yet to be determined beyond

doubt.

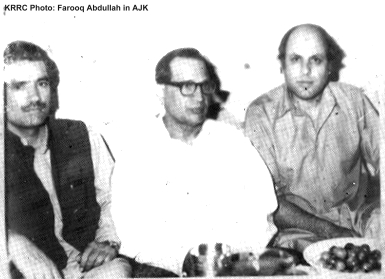

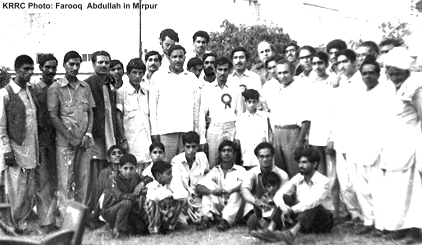

Maqbool Butt's fiercely pro-independence profile fired the imagination

of his (1960s-70s) generation in Kashmir, mainly as a vision. However,

his political following was never quantifiable, largely because that

was the time when Sheikh Abdullah's immense popularity left no space

for any other person in the hearts and minds of the people in the

Valley. Not known for tolerating 'encroachment' upon his home ground,

the Sheikh in a statement during his externment alleged that Butt's

escape from Srinagar jail (1968) had been 'arranged' by the Indian

authorities. The Sheikh's followers in Kashmir digested the allegation

despite their concurrent empathy for Butt's political philosophy.

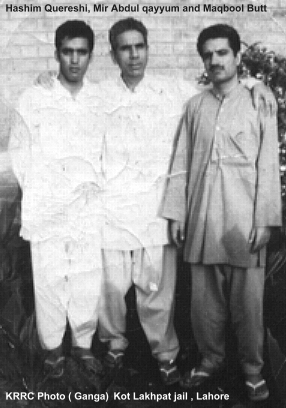

Unearthing of the pro-independence underground organization 'Al-Fatah'

in Kashmir in 1971 revealed the intensity of penetration of Butt's

influence among the Kashmiri youth. Hijacking of an Indian Airlines

Fokker Friendship plane between Srinagar and Jammu on January 30, 1971

by two Kashmiri youngmen, Hashim Qureshi and his cousin Ashraf,

followed by Butt's high profile show of solidarity with the hijackers,

along with Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's demonstrative support at Lahore

airport, enhanced the romantic appeal of the 'Butt vision' in the

Valley. India, however, viewed it as acts of 'terrorism'. Armed

insurgency in Kashmir surfaced almost two decades later, with the JKLF

in the forefront until Pakistan chose to prop up religious oriented

Hizbul Mujahideen.

This flip flop in Pakistan's attitude was evident in Butt's life time

also. Pakistan, after extracting initial political advantage of the

1971 plane hijacking, somersaulted to dub Butt as well as the two

Kashmiri (hijacker) 'freedom fighters' as 'agents' of Indian

intelligence. They were imprisoned, tortured, convicted and sentenced.

Pakistani reinterpretation of the event found its echo in a segment of

public opinion in the Valley, including the Plebiscite Front.

India, on the other hand, squarely blamed Pakistan for the hijacking

and retaliated by banning Pakistani overflights across India, between

West Pakistan and East Pakistan, in the thick of the crisis eventually

culminating in Pakistan's break up later that year.

In his widely publicized statement in the Pakistani court, Butt

categorically refuted his involvement in engineering the hijacking

though he justified his subsequent involvement with the hijackers'

cause. Whatever the truth, Butt had to pay the price. Like he had to in

an earlier incident. The court that sentenced Butt to death in 1967 for

the murder of an Indian intelligence man in Kashmir was not definite

about whether the fatal shot had been fired by Butt. There were two

other accomplices who later escaped from the jail along with Butt. He

appeared to have escaped gallows.

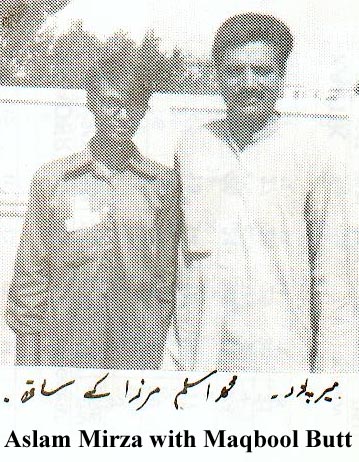

But his fatal attraction pulled him back. He intruded into Kashmir and

was rearrested in 1976 after he had shot a bank manager at Langet. He

was shifted to Delhi for security reasons where he filed an appeal

against his pending death sentence. The Indian establishment appeared

to be in no hurry to execute Butt. However, events took a dramatic fast

turn during the 8th year of his confinement in Tihar jail and there was

yet another twist in the tale, this time a very tragic one for Butt.

A militant group in the UK, calling itself 'Kashmir Liberation Army'

kidnapped Birmingham based Indian diplomat Ravindra Mhatre in February

1984 and killed him two days later after their demand for Butt's

release was rejected by India. Hashim Qureshi's book alleges that the

kidnapping and killing of the diplomat had been engineered by Amanullah

Khan, co-founder of the Kashmir Liberation Front (along with Butt) to

get Butt out of his way. Qureshi's version is that Khan was aware of

New Delhi's mind and he could foresee rejection of the kidnappers'

demand to free Butt. The trial court in Britain, however, acquitted

Khan but he was externed from the UK.

Mhatre's assassination in the UK led to immediate retaliatory execution

of Butt in Tihar jail, 17 years after he was sentenced to death by a

court in Kashmir. A dream was cut short.

Till today, there is no credible evidence involving Butt in either

planning the hijacking of the plane in 1971 or plotting the kidnapping

of the diplomat in 1984. However, his subsequent direct involvement in

the aftermath of the first incident and indirect linking of his name

with the second one proved decisive enough to result in the tragic end

of his tumultuous life.

Senior police officials who interrogated Maqbool Butt at length during

his detention in Kashmir in he 1960s and 70s say that he was unusually

'co-operative' and did not disown responsibility for what all he had

actually done. He was consistent in his commitment to 'independent

Kashmir' and never hid his almost equal disliking for both, India and

Pakistan. 'He was a dreamer'. His attachment to his motherland was

'romantic' even though he had run away from Kashmir to Pakistan when he

was only 19.

Butt was articulate and disagreed with Sheikh Abdullah's political

line, not overawed by the latter's unrivalled popular support. Butt

virtually broke off from the Muzaffarabad-based Plebiscite Front in

early 1970s and floated its armed wing 'on the Algerian pattern'. Even

the original name 'National Liberation Front' was borrowed from the

then popular Algerian freedom movement.

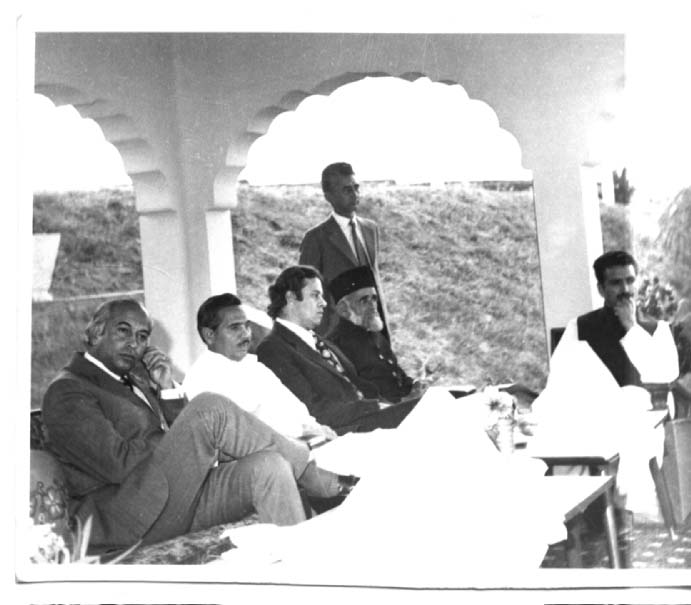

My own closest view of the Butt phenomenon in 1976 was quite a new

experience. I was the director of information in the then Sheikh

Abdullah government and was accompanying (late) Devi Das Thakur, then

finance minister, to Langet on the following day of the bank dacoity

resulting in Butt's arrest for the second time. Eyewitness account and

the police report of the incident revealed an amazing facet of Butt's

personality. It was he and his accomplice who had committed the bank

robbery 'because we needed money'. The bank manager followed them in

pursuit raising a cry and catching hold of Butt. Butt disclosed his

identity 'main Maqbool Butt hoon' and wanted the manager to let him

walk away. Finding the manager too tough to tackle, Butt who was

unarmed snatched the pistol from his accomplice and shot the bank

manager dead. A small crowd of locals pursued the fleeing duo. Butt

could have, if he wanted, shot into the crowd and fled. Instead, he

only shot into the air to scare them. The crowd did not believe him,

nor recognize him, even as he revealed his identity to them, hoping

they would let him go. Butt restrained himself, as he later told the

police. He was eventually overpowered. On the following day, we heard

the very same (eyewitness) people expressing their 'regret' over not

having recognized 'Butt Saheb'. They acknowledged that had he chosen to

fire into the crowd he could have easily managed to flee.

Retrospectively, the locals even sought to justify shooting of the bank

manager, saying 'he did not heed the warning'. This 'avoidable'

dramatic capture of Butt ultimately took him to the gallows 8 years

later. Once again, his behaviour as also its aftermath revealed the

fascinating mystique of his persona which outshines his fragmented

legacy claimed by the splintered factions of the Kashmir Liberation

Front on both sides of the LoC.